I recently had the pleasure of spending time with Dr. Mike Mew and Prof. John Mew at the London School of Orthotropics. I’ve followed the Mew’s work for a few years now, and it was particularly impressive to see their practice first hand. The jaws and dental arches of the kids who were undertaking their orthotropic program were some of the most remarkable I’d seen.

Crooked teeth or malocclusion is one of the most significant challenges on the planet, yet we don’t seem to have a united approach to address it. The Mew’s facial growth approach is not the standard of care for orthodontic practice.

It reminded me of a question I would often get from parents in the dental practice. I endured the same awkward moment again and again. A parent would bring their child for a dental check-up would ask:

“Why does my child need braces?”

I would always pause, look at the child’s mouth again and then say:

“Well, some kids just grow crooked teeth.”

Those moments were awkward because the truth was, I had no answer. I wasn’t sure why some children’s teeth wouldn’t grow straight. The topic isn’t well covered in dental training.

There’s another moment in my dental career that stands out. It’s the day I met Matthew. He brought a letter from his orthodontist, saying Matthew was about to start orthodontic treatment. The orthodontist was requesting the extraction of two premolars.

An initial exam showed that Matthew’s upper canines were slightly lacking space. His teeth were otherwise healthy and straight.

I looked at the letter again to confirm I’d read it correctly. Yes, I had. He was asking me to extract two healthy upper premolar teeth.

Extracting healthy teeth went against every instinct I had to preserve them. But I didn’t have any basis on which to refuse. Matthew obviously wanted a straight smile. The orthodontist’s treatment plan was clear.

I did perform the extractions as requested. But it felt wrong, and I thought I’d done Matthew a disservice.

Orthodontics occupies a tiny space in dental training. That’s why dentists, for the most part, refer patients needing orthodontics to specialists. Dentists are trained to broadly identify and classify crooked teeth and make a treatment plan.

Cases like Matthew’s have caused voracious debate for over 300 years. At the time, I wasn’t aware of an approach that would have treated Matthew differently. Had I known the origins of the theories behind his treatment, I may have provided a second opinion.

But you can’t understand a concept without context. Orthodontics has a checkered history when you take a closer look.

We need to understand how modern orthodontics evolved and how we should be treating oral health today. So, let’s take a rapid dive into the history of orthodontics.

The modern concept of ‘Getting Braces’

When you think of orthodontics, you probably think of braces. Brackets or braces are the most common treatment for crooked teeth. There are many ways to address the problem of crooked teeth.

The American Association of Orthodontics recommends that children should have a specialist orthodontic check-up at age 7. The AAO doesn’t advocate full orthodontic treatment at age 7. It does state that interceptive treatment may be appropriate.

Usually, a child is assessed at 7 but doesn’t undergo treatment until age 12. This is mainly because treatment is more predictable when the adult dentition is formed. One of the most significant problems in orthodontics is the relapse of therapy.

There is a growing belief that intervention is needed far earlier in a child’s development. This intervention may prevent the extraction of teeth once a child has reached age 12.

These two theories have been around since the 1700s. Since then many ideas about the best way to straighten teeth have come and gone.

Extraction vs. non-extraction orthodontic braces

Leonardo Da Vinci was the first to describe tooth form and how one tooth related to another in a ‘bite.’ He also described facial height with the nasal sinuses.

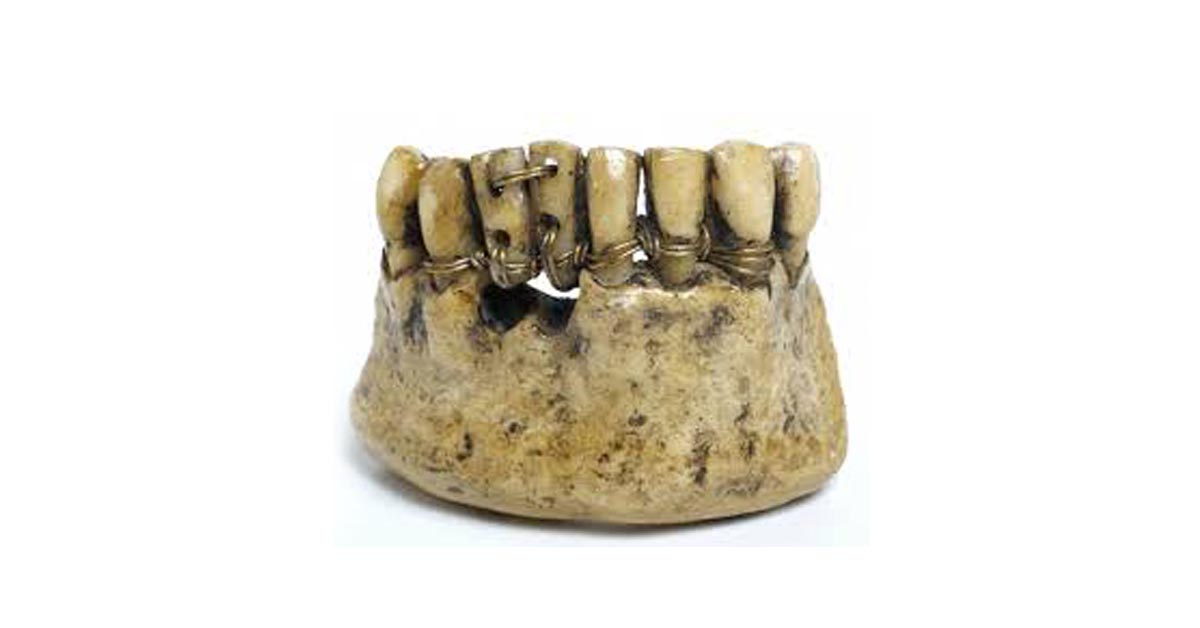

At that time, the French were already world leaders in dentistry. The French dental surgeon Robert Bunon coined the term ‘orthopedics’ during the 1700s. He advocated extraction of a number of teeth to straighten the smile. The first orthodontic appliance was made in 1723.

The extraction philosophy dominated the 18th century, with many different approaches proposed. Etienne Bourdet recommended removal of first premolars to preserve the symmetry of jaws in children with protruding chins. Extraction of adult first molars soon after eruption was also performed during this period.

But early in the 19th century, a new theory was proposed. Its advocates condemned the premature extraction of children’s teeth. They also pointed out the ignorance about the growth of the face and causes of malocclusion. Then, in 1825, Joseph Sigmond recognized oral habits as a factor in malocclusion. The idea that teeth were a product of facial growth was beginning to grow. In fact, in 1834, William Imrie was the first to suggest thumb-sucking could affect dental development.

These practitioners were the first to consider the role of lifestyle factors in malocclusion. They believed that functional habits such as tongue posture, chewing, and abnormal muscular pressure playing a role in dental growth.

The birth of modern orthodontics

In 1880, Edward Hartley Angle established the Angle School of Orthodontia in the US. The US rose to dominance in the orthodontic industry and Angle is now considered the father of modern orthodontics.

The US-based Angle was lauded as a mechanical genius. He was truly influential and more dominant than any orthodontist in Europe, where the field was born. This divide gave rise to two different definitions of orthodontics.

The US, Angle-led camp used the word ‘orthodontics’. It originates from the Greek words ‘orthos’ (straight) and ‘odontos’ (tooth). Terms such as dental orthopedics and orthopedic dentofacial were used in Europe. They reflected a broader focus on the entire facial complex. Across Europe, it was also more common to use functional growth based appliances, while the US became focused on braces based orthodontics.

Angle himself was a huge proponent of non-extraction technique and facial balance.

“The best balance, the best harmony, the best proportions of the mouth in its relation to other features, require that there shall be a full complement of teeth and that each tooth shall be made to occupy its normal position.”

To this day, the ‘Angle Classes’ are the most common way to classify a dental bite. If his teachings had proceeded more intact, a facial growth focussed approach might be more common today. But Angle’s ideals would be challenged by an influential practitioner by the name of Calvin Case. Case would lead a new group of practitioners advocating tooth extraction. There is still an academy in Case’s name that teaches his technique.

Ironically, a student of Angle, Charles H. Tweed would fuel the extraction technique further. In 1941 he introduced the concept of ‘uprighting teeth.’ He popularized the technique of extracting first premolars before orthodontic treatment. Tweed’s seminal work re-treated 40 failed non-extraction cases in the 1940s. This sparked a resurgence of extractions into the second half of the century.

Contemporary orthodontics

It was probably an Australian orthodontist who most influenced braces based orthodontics today and the common use of extractions. Percy Raymond Begg was a student of the Angle School in Pasadena, California in 1924. He later became a Professor at the University of Adelaide.

In 1928, after returning to Australia, he moved away from Angle’s philosophy. His influence, like Angle’s, was based on his technical mastery. In 1954, he created the multiple loop – a light force wire appliance – that’s still used today.

He believed in creating space to straighten the dentition. He would remove teeth and reduce the width of teeth by stripping enamel from between teeth.

The theory was based on a study of traditional Indigenous Australians. Ancestral dentitions have considerable wear due to the coarseness of a diet. Begg proposed that a lifetime of wear would result in a loss of ‘width’ of the teeth to about two premolars. The theory would be subsequently disproven but have had a lasting impact on the role of orthodontics.

During the 60s, the increase of graduates and demand meant the US orthodontic community grew from 3000 to 8500 in 1975. Begg’s theory prevailed as the zeitgeist of the profession as it matured, even though it was debated.

Since then, the industry has ballooned to an 11 billion-dollar behemoth it is today. In the US nearly 4 million kids are fitted with braces each year. Braces, with or without extractions at age 12 is the most common line of treatment.

An age-old debate comes alive

Today, the link between mouth breathing, malocclusion and orofacial function has come back into the debate. Many rightly say the literature has yet to confirm these links. However, evidence is now supporting the connection between crooked teeth, breastfeeding, mouth breathing, and sleep apnea. It suggests that functional aspects of jaw growth have a role in correcting teeth.

Facial exercises have been used since 1918 to correct mouth breathing habits. Professor John Mew, who coined the term ‘orthotropics’, is a professor at the London School of Facial Orthotropics. His concept of ‘tropics’ is rooted in the dentofacial school of thought. Its core idea is that oral posture, including chewing with lips closed, is the key to changing jaw structure. His device, the Biobloc, was one of the first modern expansion devices.

When he suggested the concept in the 70s and 80s, some people ridiculed him and labelled him a crank. It’s a sentiment still echoed by the British dental community, with Mew’s registration recently revoked.

John Mew’s work has been continued by his son, Dr. Mike Mew. Their concern is that modern braces can be retractive in nature, preventing the face from growing forward. They increase vertical growth and take the maxilla backward, giving it a longer thinner shape, a downswing in facial growth direction. The Mew’s assertion is that modern faces are a long way from what they have been in our evolutionary history.

As I looked at the patients at their practice in London, I had never seen such broad, flat palates. Both John and Mike Mew have received criticism for their views on the role of facial growth in malocclusion, but their view is growing all over the world.

Dr. Bill Hang has spent his career advocating the reversal of extraction based orthodontics. His technique aims to open up extraction sockets and regain the space lost during retractive treatment.

Dr. Derek Mahony, a Sydney-based orthodontist, and international lecturer, has been teaching dentists these concepts for 20 years. He too describes the split between conventional orthodontics and the functional aspects of crooked teeth.

Dr. Chris Farrell’s Myo Research and Myobrace system is a leading approach for myofunctional orthodontics in Australia an many other countires around the world.

Prof. Dave Singh has led a movement called ‘epigenetic orthodontics’ out of Beaverton, Portland. Singh created the DNA appliance which is showing promising application in expansive based adult-orthodontics.

Dr. Barry Raphael, a renowned airway orthodontist, based in New Jersey, recalls a large 2009 conference in Connecticut. Strongly pro-extraction and anti-extraction practitioners were pitted against each other. At the end of the event, they were asked how often they did extractions. They all said between 5-10%. Sometimes, even ardent anti-extractionists can’t find another way. However, the real numbers in the UK at least are argued to be much higher by John Mew.

The problem at the heart of conventional orthodontics is a failure to ensure long-term results. Recently, a long-term study on retainers was published showing that relapse after orthodontic treatment is to be expected, regardless of use of retainers.

Why are the teeth moving at all? There is certainly a missing functional element to dental arch development that needs broader acknowledgement.

A future without braces?

Scientists – and humans in general – are an argumentative bunch. The orthodontic debate is unlikely to be resolved anytime soon.

Today, an orthodontic approach that considers the development of the face is growing in popularity. The expanding collaboration of disciplines that consider lactation, skeletal posture, breathing retraining, and orofacial myology is producing children whose teeth are straightened without brackets.

Breathing, including the focus of nasal breathing, has been shown to influence palatal development and straight teeth. Its modern term is ‘airway’ or ‘sleep breathing’. It addresses the epidemic of sleep disorders that plague society today. In Brazil, these problems are becoming the norm rather than fringe cases. My work, which focusses on the nutritional influence on jaw growth is a further conversation we need to have about malocclusion.

As with most of the innovations in healthcare of the 20th century, orthodontics saw a rapid advance in the ability of treatments. Dentists and orthodontists today are building a functional approach with an aim to prevent crooked teeth. That includes nutritional and lifestyle factors that may ironically mean future generations do not need braces.

Now I want to hear from you. Did you have orthodontics? Does your child need braces? Leave your questions in the comment section below.

For more information on Dr. Lin’s clinical protocol that highlights the steps parents can take to prevent dental problems in their children: Click here.

Want to know more? Dr Steven Lin’s book, The Dental Diet, is available to order today. An exploration of ancestral medicine, the human microbiome and epigenetics it’s a complete guide to the mouth-body connection. Take the journey and the 40-day delicious food program for life-changing oral and whole health.

Click below to order your copy now:

US AMAZON

US Barnes & Noble

UK AMAZON

Australia BOOKTOPIA

Canada INDIGO

7 Responses

Great article, Steve.

As a 30 yr plus dentist and a senior University lecturer I am still bewildered at the stranglehold Ortho has on dentistry- it is such an experimental- for want of a better word- irreversible and potentially destructive treatment. We are in the midst of TMJD and Sleep Apnoea epidemics and are adding to this by pseudo-scientific approaches by narrowing airways and destabilizing the occlusion.

Leave those kids alone – Let ’em grow and then see what happens…. they might get better… what a disaster that would be for our Ortho friends.

Hi Steve, I agree, a great article. I was fortunate to learn from John Mew back in the early 80’s. At that time I was also studying with Harold Gelb and Aelred Fonder so my training was at that time, primarily with adults. This raised a question for me, why did healthy children become sick adults. Then came the realisation that many of these adults already had problems in childhood that appeared to be compounded by premolar extractions. While I agree with John that extraction orthodontics changes faces, I believe that we have been missing the point. Starting early is key, early diagnosis, early gentle intervention, ensuring a good airway, correct tongue position, nose breathing and posture. Correcting cranial and spinal faults through cranio – sacral therapy and of course dietary considerations, puts care back into the hands of parents, with practitioners supporting the growth of the child.

Very interesting article – I often do not understand why so many children require braces other than the pursuit of perfection, whatever that may be (a little like the current obsession with artificially bright white teeth – don’t get me started!)

I had teeth removed as a child to allow for my teeth to grow reasonably straight and my partner has a pronounced under bite yet our three children – 15, 17 and 19 – all have beautiful smiles without the aid of braces or the removal of teeth. I consider us to be very fortunate!

Hi Dr Lin, Thank you for everything you’re doing and for your amazing book The Dental Diet. Our 7 year old has developed a deep overbite and unfortunately also has 3 hypomineralised molars. One of which is severe, while the other two are mild. The orthodontist recommends a removable appliance at age 8, followed by extraction of all 4 pre-molars and then braces, on condition molars and wisdom teeth are present in x-ray. And if not present, our child will require a lifetime of maintenance on the hypomin teeth and the same orthodontic procedure. Do you know whether Orthotropics could offer a better solution in our child’s case? We live in hope that Electrically Assisted Enhanced Remineralisation (EAER) from London Kings College will get to the market in time for our child. Currently predicted for 2022. It uses a tiny electrical current of a few micro Amps, that don’t cause any physical sensation in the patient, to introduce natural minerals back into the clean lesion. The electrical field pushes the mineral ions into the cavity, triggering remineralization from the deepest part of the lesion. Driving healthy calcium and phosphate minerals into enamel, and through a natural process it will bind on and add to the enamel that’s there.

Interstingly I had orthodontics at age 12 to treat overjet from thumb sucking. It included removable appliance, head gear, braces, retainer appliance and retaining wire behind bottom teeth to finish. All retainers were then removed. I have no retaining wires since then and my teeth havent moved in 20 years. I did have 4 impacted wisdom teeth removed at age 21 but have no head ache or airway problems. Im confused how its possible I havent needed retainers when they seem to be standard practice today?

I hope its acceptable that I ask one more question. As my 7 year old’s facial development is at stake based on my decision, its pretty much all I think about! If non-extraction and facial growth treatments have been around since 1825, how come the extraction orthodontists state that the main negative of treatments such as orthotropics is that it isnt gold standard research? Is non-extraction less scientifically proven or evidence based?

Glad to see the move away from routine extractions. It is now expected that molars need to be removed. TOT , tmTethered Oral Tissue plays a huge part in this story. Pressure from ties cause teeth to move, gums to recede, palates to not flatten, tongue to not lift, dental ridge to remain small not allowing room for molars, please address ties first before making other changes. Releasing ties at birth and breastfeeding is the first step in oral function.